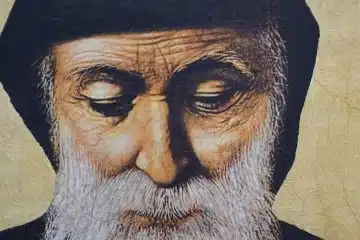

Love that Moves the Sun and Stars

A Closer Look | Kenneth Craycraft

In the 33rd and final canto of Dante’s epic 14th century poem, Paradiso, St. Bernard guides Dante to the destination of his pilgrimage, where he achieves the Beatific Vision. Dante describes his final ascent to Paradise in terms of the restoration of balance, harmony and order—heavenly perfection, one might say. But he could not achieve this vision with his own unaided sight. Indeed, the harmony of Heaven was foreign to his fallen human perception. Similar to the mathematician’s inability to “square the circle” (failure to find a formula to convert the area of a circle to the exact area of a square) Dante could not see the harmony of the universe with his own eyes of finite and fallen reason.

As a geometer struggles all he can

to measure out the circle by the square,

but all his cogitation cannot gain

The principle he lacks: so did I stare

at this strange sight, to make the image fit

the aureole, and see it enter there.

His inability to grasp the harmony of Heaven on his own caused Dante to realize the futility of trying to know and love God through his own feeble effort. He could not make the final ascent on his own; he had to be carried to the ultimate destination of rest in God.

But my own wings were not enough for this flight,

Save that the truth I longed for came to me,

smiting my mind like lightning flashing bright.

Dante discovered two truths as he approached both the Heavenly vision and the end of his poem. The first is that his effort alone is not sufficient to scale the heights of the celestial realm. He cannot square the circle. But the second truth was revealed to him simultaneously with the first. The truth he sought was not accessible by his own effort, but it was attainable by the helping grace of God. Both truths “smote” his mind. The penny dropped. He had his “aha” moment. And the result was his ultimate surrender to the love of God.

Here ceased the powers of my high fantasy.

Already were all my will and my desires

Turned—as a wheel in equal balance—by

The Love that moves the sun and the other stars.

The square was circled; equilibrium was restored.

This most famous stanza in all of The Divine Comedy illustrates Dante’s understanding that when all has been finally consummated, one power will be revealed to prevail above all things. It was love that created the universe; love that sent the Son to redeem fallen creation; and love that finally orders all things “as a wheel in equal balance.” This tells us nothing less than that we have a divine mandate to consider love the sole motivating principle of our lives.

But what is love? And how is it expressed in the Christian tradition? The most common answer is drawn from St. Thomas Aquinas. “To love,” the Angelic Doctor explained, “is to wish good to someone.” This is the “default” definition in any Catholic discussion of love. Love is the virtue of willing the good for another. Indeed, in Dante’s native Italian, a common way to tell someone you love them is to say, “ti voglio bene”—literally, “I wish you good.” This is commonly thought of as “Platonic” love, a term of warm, heartfelt affection for very close friends or members of one’s family.

But while a very good definition, it doesn’t quite work in the context of the ultimate stanza of Paradiso. To will the good of someone implies the potentiality of some lack of good in that person. But that makes no sense if God—who is all good—is the object of our love. Thus, “I wish you good” is neither the expression nor the meaning of the last line of Dante’s epic poem, which uses the Italian word “amore,” as in “l’amor che move il sole e l’altre stelle.”

Amor and Eros

To understand that love, “the love that moves the sun and the other stars,” it is helpful to invoke one of the (at least) four Greek words for love: eros, the rough equivalent of the Italian amore. Indeed, Eros and Amore are the respective Greek and Roman names for the god of love and desire.

In common English usage, we typically think of eros as the root for our word “erotic,” and we usually define it very narrowly as something like romantic sexual attraction (or even forbidden pleasure). But as a rough equivalent of the Italian amore, eros has a much broader definition in classical and historical Christian usage. Eros is not confined merely to sexual attraction (often confused with lust). Rather, eros is properly understood as the faculty by which we are attracted to any object we desire, and from which we expect pleasure or satisfaction. In this sense, it is appropriate to express our love for God as a form of eros. Eros is the motivating faculty for moving toward our desire.

And what greater desire can we have than to be in the presence of God? Of course, many of us are familiar with another Greek word for love, “agape.” Indeed, this is the word that Christ uses to describe the greatest commandment, to love God and our neighbor, in Matthew 22:37-39. This is the kind of objective, dispassionate, unconditional love that corresponds to the theological virtue of charity. But Dante teaches us that it is not just proper, but very good, to desire God as the lover pines for his beloved. That is the “love that moves the sun and the other stars.”

Dr. Kenneth Craycraft holds the James J. Gardner Chair of Moral Theology at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary & School of Theology. He is the author of Citizens Yet Strangers: Living Authentically Catholic in a Divided America. He is the host of Driving Home the Faith on Sacred Heart Radio.

Dr. Kenneth Craycraft holds the James J. Gardner Chair of Moral Theology at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary & School of Theology. He is the author of Citizens Yet Strangers: Living Authentically Catholic in a Divided America. He is the host of Driving Home the Faith on Sacred Heart Radio.

This article appeared in the February 2026 edition of The Catholic Telegraph Magazine. For your complimentary subscription, click here.