Called to Discipleship

In a visually saturated world, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed and become desensitized to beauty. Visio Divina, Latin for “divine seeing,” encourages us to slow down and engage in visual contemplation, using art as a profound tool for connecting with the Divine.

A Guide to Visio Divina

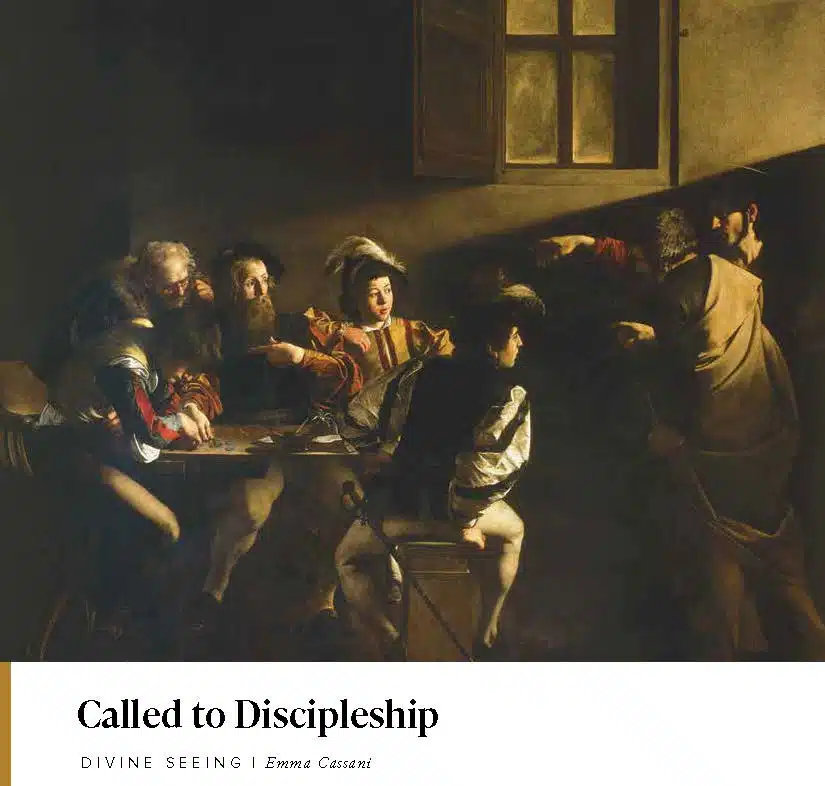

Begin by making the sign of the cross and inviting the Holy Spirit to guide your contemplation. Spend a moment meditating on The Calling of St. Matthew, ca. 1600 (Baroque Period) by Caravaggio, located in the Contrarelli Chapel at San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome. Then, read Matthew 9:9-13 (also seen in Luke 5:27-32 and Mark 2:13-17).

Background

Michelangelo Merisi—more commonly known as Caravaggio, after his hometown in Lombardy—was born on September 29, 1571, on the Feast of St. Michael the Archangel. Orphaned by age 11, Caravaggio was taken in by a painter in Milan, where he began to learn chiaroscuro and tenebrism, two dramatic lighting techniques that would become his signature.

Caravaggio would go on to become one of the most influential painters of the Baroque movement, known for his lifelike, theatrical, and emotionally charged depictions of the life of Christ and His disciples. But in sharp contrast to the sacred subject matter he often painted, his personal life was chaotic and scandalous. He was notorious for provoking fights, swindling money, carrying a sword illegally, and fleeing from murder charges. Perhaps most strangely—and somewhat comically—he once assaulted a waiter with a piping hot dish of artichokes after being displeased with his meal.

This begs the question: How could someone live a life at odds with the Gospel yet produce such spiritually rich art? Did the faith genuinely inspire Caravaggio, or was painting merely seen as a means to a profitable end?

Enter In

Tucked away in a shadowy corner of an old tavern, a group of tax collectors huddle as outcasts, counting their earnings from the day. Slow and calculated, a man slides his money onto the wooden table—each coin landing with a hollow clink. Loose silver, ledgers, and the weight of greed clutter the space between them.

Suddenly, they are interrupted by a soft beam of light that spills into the tavern, slicing through its deep shadows. The light doesn’t flood the space; it only illuminates a few faces. Two men emerge from the direction of the light. One steps forward, barely. His face turned, his body half- concealed behind the other. A hairline halo hovers over his head, so faint it could be missed. His robe blends into the shadowed wall behind him. This man, Jesus, seems hidden, nearly absorbed by the space. His hand extends—not in a grand gesture—something quiet yet deliberate. Between the viewer and Christ stands Peter, representing the Vicar of Christ, guiding the Church between her people and the Savior.

The beam of light above Jesus guides the viewer’s eye diagonally down to Matthew. Its source is unseen, reaching beyond the frame. Jesus is not the source of light, nor is He brightly illuminated. Instead, the light comes from above—not from the grainy window—but perhaps, from God the Father.

Matthew, Mark, and Luke all write in the gospels that Matthew immediately rose and followed Jesus. Caravaggio, instead, lingers in the respite. Rather than leaping up, Matthew sits, one hand caught mid-count over the coins. His other hand lifts slowly toward his chest—not quite in disbelief, not quite in protest. His wide eyes remain calmly fixed on Jesus. He doesn’t speak, but the question is clear: Me?

This moment feels undeniably human: full of hesitation, vulnerability, and unworthiness. Still, Jesus waits. His hand, raised yet relaxed, echoes the gesture from Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam. Except here, it is not the Father’s hand Jesus mimics, but Adam’s. Christ, the Second Adam, reaches into Matthew’s world of darkness, instant gratification, greed, and self-pity, and calls on him mercifully, drawing him out into grace.

Reflection

What does it mean to be a disciple, and how do we become one? Pope Benedict XVI offers a clear answer: “You cannot make yourself a disciple—it is an event of election, a free decision of the Lord’s will” (Jesus of Nazareth, 170). Discipleship isn’t a self-appointed title or an achievement. It begins with Christ’s call and becomes real only in our response.

But like Matthew, many of us feel unworthy of that call. We get caught up in our own distractions, doubts, and the weight of our sin. When Jesus calls, many of us respond with hesitation rather than confidence—mirroring Matthew asking the Lord: Me? Are you sure? The Gospel of Mark tells us that “Jesus called to Him those whom He desired” (Mk. 3:13). It is not about whether we feel worthy to receive His grace; it is about His desire for us. But in order to respond, we must be open to receive.

Caravaggio’s The Calling of St. Matthew beautifully reveals the tension within every human heart: the darkness of sin and shame, the mesmerizing light of Christ, and the quiet struggle between clinging to what we know or surrendering to what we truly desire.

I can’t help but wonder if Caravaggio, while painting this piece, saw himself as Matthew. He was an outcast, a fugitive on the run, and a hot-tempered man. Someone who wrestled with the allure of sin and seemed least likely to be called by Christ. Moreover, Caravaggio invites us into the painting by leaving room at the tax collector’s table. We can truly “enter in” and imagine ourselves in this scene. Perhaps the artist is asking: How would you respond to Jesus’ call?

Emma Cassani, [email protected], is the graphic designer behind The Catholic Telegraph. She is passionate about exploring the intersection between art and faith

Emma Cassani, [email protected], is the graphic designer behind The Catholic Telegraph. She is passionate about exploring the intersection between art and faith

This article appeared in the May 2025 edition of The Catholic Telegraph Magazine. For your complimentary subscription, click here.