Father Clarence Rivers

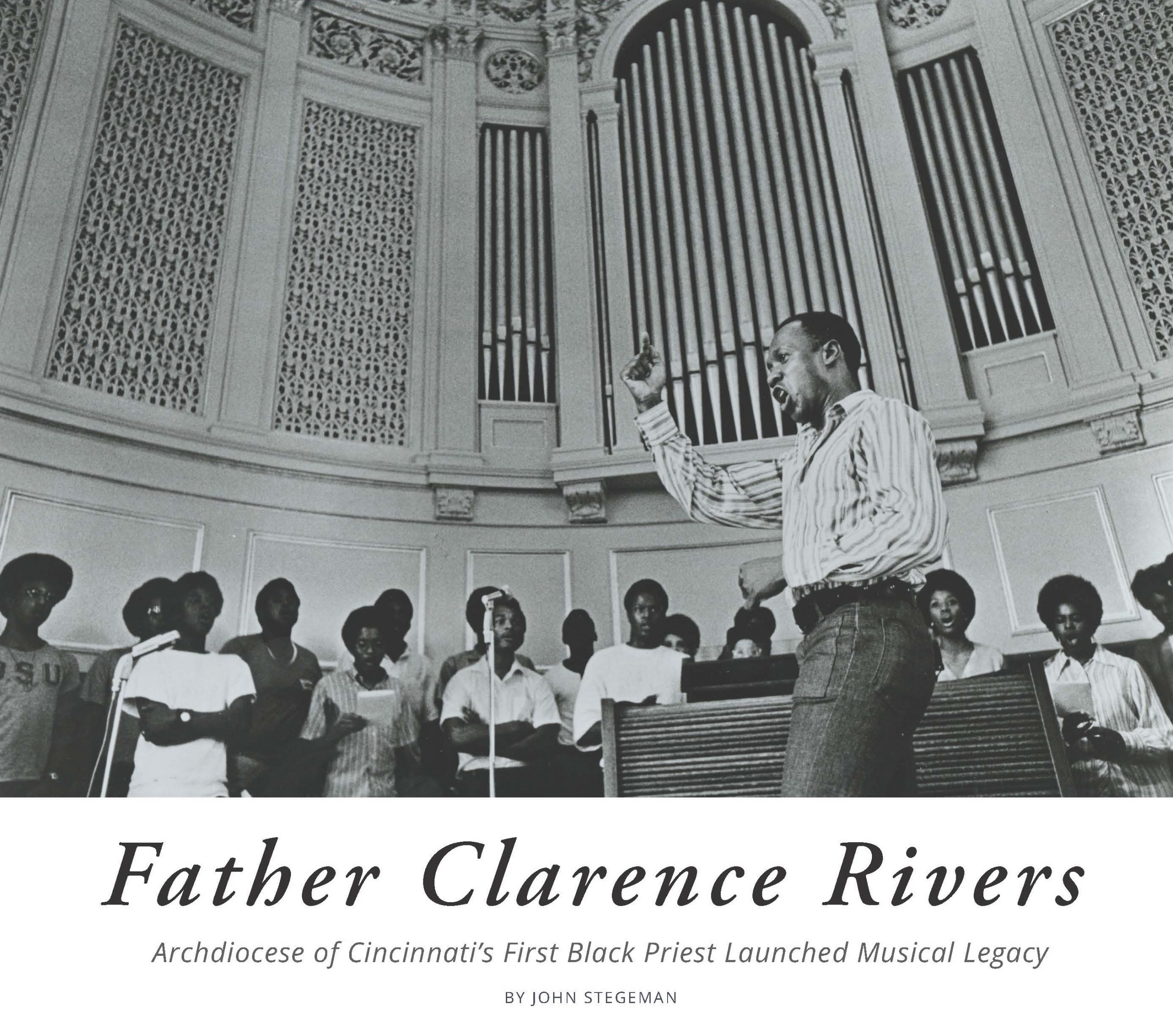

Father Clarence J. Rivers was the first Black priest ordained in the Archdiocese of Cincinnati. He is a nationally known figure in Catholic music and liturgy and was an iconic figure for the Black Catholic community throughout the country. Father Rivers died in 2004, but his influence is still perceptible throughout the archdiocese and beyond.

“When Black Catholics around the United States reflect on the inculturation of Black spirituality [music, art, movement, prayer and faith], Father Rivers is the name that rises to the top,” said Deacon Royce Winters, director of African American Pastoral Ministries for the archdiocese and pastoral administrator at the Church of the Resurrection in Bond Hill. “The local Black Catholic communities in the U.S. and in this archdiocese have continued to carry on the legacy of inculturation which began with Father Rivers.”

Father Rivers was born in Selma, AL, but his family moved to Cincinnati when he was young. He attended St. Gregory and Mount St. Mary’s Seminaries and was ordained to the priesthood on May 26, 1956. His was an associate pastor at St. Joseph’s in Cincinnati’s West End and spent time teaching at Purcell High School. He later served at Assumption in Walnut Hills. In 1965, the archdiocese released him from his assignments to pursue his program of inculturation of African American culture in Catholic worship.

He went on to become known as a liturgical artist, composer and author. Perhaps his best-known hymn, “God is Love,” was sung at the 1964 National Liturgical Conference during the first High Mass said in English in the U.S. Catholic Church. After the song, the assembly applauded for 10 minutes.

Father Rivers spoke out on the need for his ministry. In a 1977 article in The Catholic Telegraph, he said that, to some people, the Church “is one big happy family and any giving in to ethnic concerns is wrong. To them, there is one faith, one Baptism, one Church and one culture – namely, European.”

Deacon Winters, who called Father Rivers a friend, feels his legacy in his own continued ministry.

“In 1978, as my family and I searched for a church home, we attended Saint Agnes Church,” Deacon Winters said. “Father Rivers was serving as the guest homilist, and he preached about racial injustice. I spoke to him afterwards because I was disturbed about his message. I was seeking the Christ, and he was preaching about racial injustice. Father Rivers invited me to his home, and we began a lasting friendship. After my ordination, he would often call me and say, ‘I need my deacon.’ I would accompany him to various dioceses for liturgical services and workshops, serving as his deacon and cantor. Father Rivers was instrumental in my liturgical formation and the freedom to embrace the culture of being authentically Black and Catholic.”

In his obituary in the Cincinnati Enquirer, Father Rivers’ sister said, “Although small in physical stature, he had a presence that was larger than life. Once he entered a room or a gathering, you knew you were in the midst of someone extraordinary.”

This article appeared in the June 2021 Bicentennial Edition of The Catholic Telegraph Magazine. For your complimentary subscription, click here.