Haiti: A journey of the heart

May 18, 2011

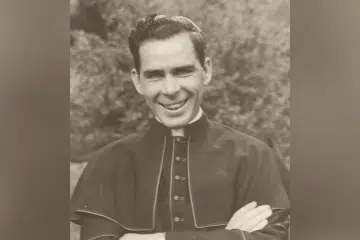

Recently, at the age of 89, Cincinnati priest Father Joseph Beckman was asked to make his 13th trip to Haiti since 1973. It has been a turbulent 17 months for the impoverished island nation, still recovering from a January 2010 earthquake that left 300,000 persons dead and another 1.5 million homeless. In March, exiled former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide — a laicized priest — returned to Haiti to work on education issues in his native land.

Father Beckman accepted the invitation to make the difficult trip because he said he wanted to see if any progress has been made “in the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere” since 1973. He also wanted to see the difference that Catholic parishes in the United States have made through their twinning programs, so he traveled with Theresa Patterson, executive director of the Parish Twinning Program of the Americas.

Upon his return, he shared his story with The Catholic Telegraph.

Article and photos by Father Joseph Beckman

Getting to Haiti itself is an ordeal of bedlam proportions: a 40-minute wait in the airport security line in Miami; less than a two-hour flight in a large, crowded plane, and a 50-minute experience of rescuing your baggage at the somewhat less-than-organized airport in the capital city of Port-au-Prince. Then it’s a bumper-to-bumper trip by van over crowded, unpaved and rocky streets, to Matthew 25, the guesthouse of the twinning program, which can accommodate up to 35 persons.

I joined a group from the Sioux City diocese, the Iowa diocese where Archbishop Dennis Schnurr was born and grew up. Father Ed Girres and five of his parishioners were traveling to Chantal, a town of some 1,900, just beyond Les Cayes, in the southwest corner of Haiti, to visit their twin parish, St. Jeanne de Chantal, for the first time.

On my first day I wanted to visit the Catholic and Episcopal cathedrals and the diocesan seminary where seven of the 30 Haitian seminarians who died in the earthquake lost their lives.

|

| The rubble of the Haitian seminary, where seven seminarians died in 2010. |

The Catholic cathedral was a bombed-out shell, with piles of earthquake debris still on the front steps. I remembered attending a 4 a.m. Sunday Mass at the cathedral, which was the “poor people’s Mass,” because they didn’t have decent clothes to come in daylight.

I used to take visitors to the Episcopal Holy Trinity Cathedral to view some elegant Bible-scene murals painted by some of Haiti’s most prominent artists. This lovely cathedral, too, was totally demolished.

The seminary was still a total pile of rubble. The seven young men who died there are buried under a statue of our Blessed Lady, where they had often gone to pray.

I had lunch at the old-fashioned Oloffson Hotel, which writers and theatre people loved to frequent in the 1970s. Tourism in those days was 22 percent of Haiti’s business income. Cruise ships used to dock frequently at Port-au-Prince. Today, the only tourists in Haiti are religious groups who come to help with the earthquake and poverty problems.

I asked our Haitian waiter, who had been working at the Oloffson for 28 years, why the hotel had not been destroyed in the earthquake.

“It was the grace of God,” he replied, testifying to the deep faith of many Haitians.

|

| Father Ed Girres of Sioux City, second from left, and Theresa Patterson, far right, speak with local Haitians about the devastation from the earthquake. |

The next day I joined Theresa Patterson and the group from Iowa for a five-hour trip to Chantal. It was bumper-to-bumper for two hours getting out of Port-au-Prince. We passed countless destroyed buildings and temporary tent cities as we headed westward for 130 miles. We detoured through a riverbed, as one major bridge was too dangerous to drive across.

About two-thirds of the way to Les Cayes, the earthquake damage lessened. The city’s 50,000 residents had felt the earthquake but suffered no major damage.

The last few miles to Chantal were traveled on a rocky dirt road. Father Jocelyn Misalier, the Haitian pastor of Ste. Jeanne de Chantal, welcomed us to his parish.

One major purpose of our visit was to let the Iowa parishioners learn of the needs of their Haitian twin. Another purpose served to contrast the living conditions in the United States with the overall stark poverty of Haiti.

Father Girres is pastor of St. Cecilia Parish in Algona, Iowa, a town of about 5,200 persons. “Algona is an area of subsistent farmers of deep faith, and each weekend 1,200 people attend one Saturday and two Sunday Masses,” he said.

|

| The Catholic Cathedral of Our Lady of the Assumption in Port-au-Prince. |

Father Jocelyn, 54, a native Haitian, has been a priest for 24 years. His current parish was founded in 1912 by Oblate of Mary Immaculate missionaries. The 9 a.m. Sunday Mass overflows with parishioners who dress up in their Sunday best. He also cares for 10 chapels in the surrounding area. On Sundays he celebrates at least one Mass in one of the chapels, and he visits the others as often as he can on weekdays.

One afternoon he drove us into the Haitian mountains to one of the chapels over the roughest road I had ever been on. Part of the chapel roof had been blown off during a windstorm and needed repairs. He is only able to visit this chapel once every two months for Mass.

The parish also has a large school. Haiti has no free public school system. Most schools are private — many connect with a parish — and students must pay tuition. As a sad result, perhaps 60 percent of Haiti’s children get no education other than on the streets where they live.

In four days in Chantal our group visited all of the parish school classrooms, a large open-air market, a nearby health clinic and three of the outlying chapels. We also we met the mayor of Chantal, and our visit ended with a crowded Mass on Sunday morning.

I had attended a 6 a.m. daily Mass and was quite edified by the a cappella singing and participation of about 25 parishioners at each Mass. The music at the Sunday Mass was led by a fine guitarist and two men playing drums.

|

| Tent cities remain the only dwellings for many residents; they are primitive structures with no running water, heat or cooling. Sanitation remains a primary problem in Haiti. |

Theresa Patterson says that visits like ours to Chantal are the real heart and soul of the Parish Twinning Program, which is my favorite Haitian charity. Three hundred and forty U.S. parishes have twinned with Haitian parishes or projects since 1978 and have provided $30 million in aid through the years.

I was totally edified by Father Jocelyn’s dedication and zeal and also by Father Girres’ Iowa group, most of whom had never been in the Third World before.

More information can be found about The Parish Twinning Program of the Americas on the website at www.parishprogram.org.

|

|

| Father Jocelyn Missalier with some of the students in his parish school. | Father Joe Beckman with a Haitian pastor who spent 10 years in Cuba. |

|

|

| Seven seminarians are buried under the statue of Mary at which they often prayed. | Haitians dress in their Sunday best for Mass at St. Jeanne de Chantal Church. |