Walking with Christ

In a visually saturated world, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed and become desensitized to beauty. Visio Divina, Latin for “divine seeing,” encourages us to slow down and engage in visual contemplation, using art as a profound tool for connecting with the Divine.

In a visually saturated world, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed and become desensitized to beauty. Visio Divina, Latin for “divine seeing,” encourages us to slow down and engage in visual contemplation, using art as a profound tool for connecting with the Divine.

A Guide to Visio Divina

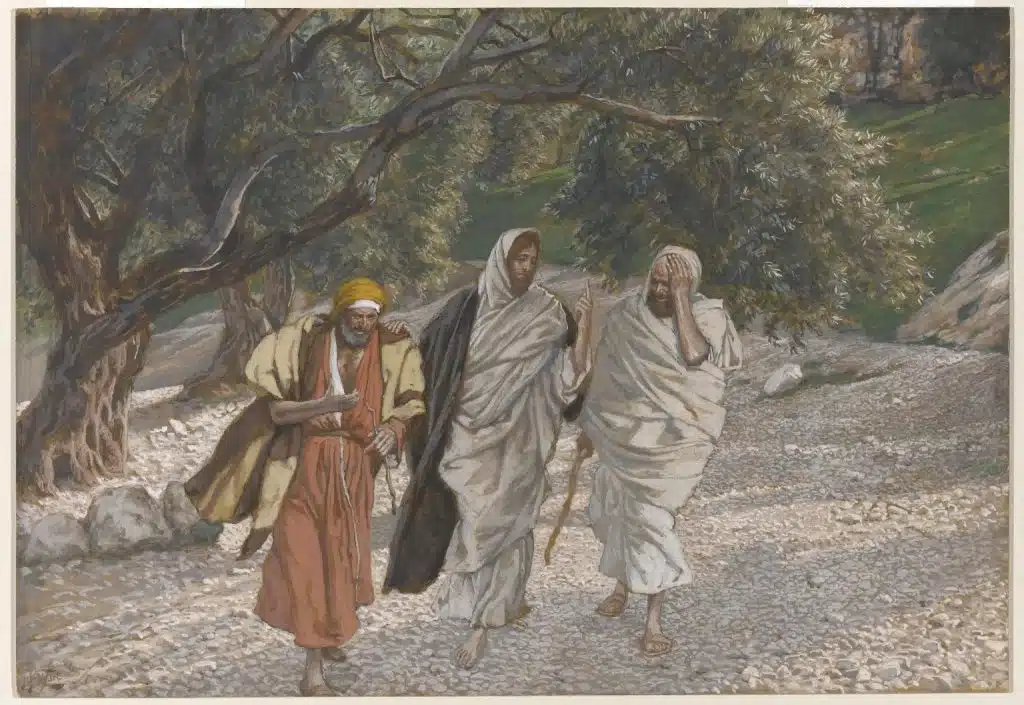

Begin by making the sign of the cross and inviting the Holy Spirit to guide your contemplation. Spend a moment meditating on The Pilgrims on the Road to Emmaus, ca. 1886-94, by James Tissot, located in the Brooklyn Museum. Then, read Luke 24:13-35.

Background

Jacques Joseph (James) Tissot was born in Nantes, France, in 1836. A devout Catholic, his mother instilled the faith in him from an early age. Both parents worked in the family drapery business, and his mother also designed hats. This likely influenced Tissot’s work, who often painted women’s clothing with remarkable detail. By age 17, Tissot knew he wanted to pursue art as a profession, a

decision supported by his mother but not his father. He moved to Paris in 1856, enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts, began exhibiting at the Paris Salon in 1859, and there met Manet and Degas.

Although trained in academic and realist art, Tissot produced many of his most recognizable works during the Post- Impressionist era. He planned to return to painting fashionable Parisian women but had a profound conversion experience during Mass when he saw a vision of Jesus tending to people in a ruined building. Tissot then dedicated himself to illustrating Biblical scenes. While his technique occasionally reflected looser brushwork and the post- impressionists’ quiet, dreamy settings, his style ultimately transcended the movement, especially in later religious paintings, which combined historical and narrative accuracy with profound reverence.

Accuracy was so important to him that he traveled in 1886 to the Holy Land to begin a series on The Life of Our Lord Jesus Christ. This collection comprised more than 350 watercolor paintings created over approximately 10 years.

Enter In

Beneath the olive trees’ twisted trunks and silver-green canopy, two disciples tread along the rocky path from Jerusalem to Emmaus. Cleopas and his companion had been mourning with the other disciples when the women arrived joyfully announcing the empty tomb. They shared the angels’ appearance and proclamation that Jesus had risen from the dead.

However, weighed down by sorrow and uncertainty, the two men saw no reason to stay in Jerusalem. The painter captures them trudging home to their village, leaning on walking sticks, as they try to make sense of recent events.

Suddenly, a barefoot traveler wrapped in white garments and a black cloak approaches them. He requests to walk with them and inquires about their conversation. Cleopas, clearly annoyed, responds, “Are you the only visitor to Jerusalem who doesn’t know what’s happened these past few days?”

Jesus plays along. “What sort of things?”

With aching hearts, they recount Christ’s Passion, mentioning that some even believe He rose from the dead. They share that they “had hoped [for] great things [like the salvation of Israel], but God had disappointed them” (Sheen, Life of Christ, 412). Though their minds hold the facts, their hearts remain unconvinced.

Jesus speaks more plainly this time, “Oh, how foolish you are! How slow of heart to believe all that the prophets spoke!” As Venerable Fulton Sheen explains, these disciples “are accused of being foolish and slow of heart because, if they had ever sat down and examined what the prophets had said about the Messiah—that He would be led like a lamb to slaughter—they would have been confirmed in their belief ” (Sheen, Life of Christ, 413). They still do not recognize Jesus, but begin to catch on when He explains all in Scripture that points to Him (Lk. 24:27). At this moment, their hearts begin to burn, although only later, when He breaks the bread, do they fully recognize Jesus.

As we focus on the figures in Tissot’s painting, Jesus stands in the center between the two disciples: Cleopas, on the viewer’s right, and his unnamed companion on the left. Their clothing is quite interesting and initially puzzling, but given Tissot’s keen appreciation for fashion, he likely chose their attire intentionally.

First, consider Jesus. He wears white, symbolically referencing His Resurrection—new life. Yet, a black shroud drapes over his shoulders, signifying His death and acting like a veil, spiritually concealing His identity from His disciples. His garments are not a traveler’s typical attire; rather, they resemble burial cloths, as though He freshly emerged from the tomb.

Cleopas’ attire closely mirrors those of Jesus, though wrapped more tautly. His unyielding garments suggest someone still bound by earthly distractions, not yet fully awakened by the truth of Christ’s Resurrection. Cleopas’ journey toward spiritual enlightenment is still in progress. He is tightly restrained by his doubts.

In contrast, Cleopas’ companion is clad in culturally accurate clothing. His robe is dyed a clay-red and brown reminiscent of dirt that may imply his earthly struggles. Touches of yellow in his clothing may indicate sin or betrayal, as Christian art often depicts Judas. The disciple’s face twists in confusion, his mind straining to make sense of the mystery unfolding before him. He seems to walk ahead of the others, as though his anxieties are carrying him away. Yet, even while the companion agonizes, Jesus’ steady hand rests on his shoulder, gently pulling him back—as if to say, “Slow down; walk with Me.” The disciple’s open, loose garments suggest that, while confused, he remains receptive to Jesus. He is not alone and is steadily moving toward understanding.

Their differing garments seem to visually express the disciples’ inner spiritual states and distinct natures of their journeys toward belief. Though both abandoned their faith in Jerusalem and struggle to recognize the risen Christ, their doubt takes different forms. Christ, with infinite patience, accompanies them over the seven-mile road, gently guiding them and gradually revealing Himself.

Reflection

The two disciples have given up and are walking away from Jerusalem—or as Bishop Barron puts it, away from salvation itself. Full of grief, confusion, and despair, they cannot comprehend the Resurrection and assume that God has abandoned them. Jesus meets them where they are. He humbly walks alongside them. Though they do not recognize Him, He is with them the entire time.

At the breaking of the bread in Emmaus, Jesus fully reveals Himself. The moment the disciples recognize His true identity, Jesus vanishes from their sight. This disappearance is not a loss but a moment of renewed faith. Cleopas and his companion regain their belief and return to Jerusalem.

During times of distress or even in the rhythm of daily life, do we recognize Jesus’ presence? Like the two pilgrims, we often fail to see the extraordinary in the ordinary; our hearts slow to believe. In actuality, we are constantly surrounded by the extraordinary. Jesus is here. He will always be near, gently guiding and slowly revealing Himself to us.

Tissot does more than depict a moment from Scripture—he invites us into it. Through his meticulous attention to gesture, expression, and clothing, he captures the reality of the spiritual journey. In our own seasons of sorrow, confusion, or even routine, we might—like the two disciples—fail to perceive the presence of Christ. Yet, He walks beside us, ready to reply to the questions of our aching hearts. Perhaps Tissot leaves us with this question: Will we recognize Jesus in the mundane, in the stranger on the road, or at Mass in the Eucharist?

Emma Cassani [email protected] is the graphic designer behind The Catholic Telegraph. She is passionate about exploring the intersection between art and faith.

Emma Cassani [email protected] is the graphic designer behind The Catholic Telegraph. She is passionate about exploring the intersection between art and faith.

This article appeared in the June 2025 edition of The Catholic Telegraph Magazine. For your complimentary subscription, click here.