A Closer Look: The Dignity and Purpose of Work

In 1955, Pope Pius IX established May 1 as the Feast of St. Joseph the Worker, a day set aside to seek St. Joseph’s intercession on behalf of laborers. The date was chosen as an alternative to International Workers’ Day, to celebrate workers while avoiding association with May Day’s historical Marxist inflection. Although many countries still celebrate May 1 as Labor Day, for Catholics, the Feast of St. Joseph the Worker is the day to recognize and celebrate the dignity of work and workers without subscribing to the errors of collectivist political economic theories. And, of course, it reminds us that we must always be mindful of a proper understanding of the nature and purpose of work.

In his classic 1901 memoir, Up From Slavery, Booker T. Washington reflected on labor’s value by recalling his days as a student and janitor at Hampton Institute (now Hampton University).

“At Hampton,” Washington wrote, “I not only learned that it was not a disgrace to labor, but learned to love labor.” He learned to love work for its “own sake” as well as the satisfaction of supplying goods and services to others. Through physical labor, he wrote, “I got my first taste of what it meant to live a life of unselfishness” and to discover the happiness that can be found in providing services to others.

Later, Washington and his students made and laid the literal bricks that became Tuskegee University, while the students also labored in agricultural work as part of the curriculum. The purpose, he recounted, was so that “the students themselves would be taught to see not only utility in labor, but beauty and dignity.” They would learn “how to lift labor from mere drudgery and toil, and would learn to love work for its own sake.”

In describing work’s value both for “its own sake” and for the purpose of serving others, Washington expresses essential elements in the Catholic understanding of work, especially as articulated by Pope St. John Paul II in his 1981 encyclical, Laborem Exercens. St. John Paul expounded both the “objective” and “subjective” natures of work, finding dignity in both, but elevating the latter as the greater part. “The subjective dimension of work must take precedent over the objective dimension,” he wrote.

Objectively, work is the good, service or product formed by human effort. The object is some thing, external to the worker, that can be used by another person. But work’s deeper dignity is found in the subjective sense, intimated by Washington and expressly articulated by St. John Paul.

In this sense, work is a means of “self-realization.” Work’s higher dignity is realized in the creativity and diligence that goes into the work by the human person, rather than merely the product that comes out. Understood this way, human work not only proceeds from the person, but contributes to her own moral and social development. The greater purpose of work is the flourishing of the human subject who performs it.

St. John Paul’s emphasis on the subjective nature of work helps us see the dignity in work where the produced outcome might not seem dignified. By emphasizing the worker’s moral development, we can see that dignity is found in all aspects of human labor, regardless of the objective product or service provided. This celebration of the subjective human dignity found in work is nicely illustrated in Alice McDermott’s novel, The Ninth Hour.

Set in early 20th Century Brooklyn, the novel’s protagonist, Annie, is a young woman who becomes a widow suddenly, close to the birth of her child, Sally. Having no other means of support, Annie accepts a job in the basement laundry of a local convent where nursing nuns serve the sick and dying. The objects of Annie’s work certainly do not seem very dignified. Every day, she washes “the stained bedclothes of the sick,” and her duties include the nuns’ routine laundry. “Whatever troubles the Sisters encountered in their daily work were illustrated by the stains on an apron or a sleeve—the odor of vomit on wool, a spattering of blood across a white bib.” Annie’s days are filled with saliva, mucus, blood, urine and feces, yet she discovers her own labor’s dignity, becoming a witness to the subjective goodness and worth of the objectively “undignified” work of tending the sick and cleaning up after them. For Annie, the work becomes not just an end in itself, but also the means to serve others while contributing to her own moral development.

This is the “subjective” nature of work, in which the laborer’s good is greater than labor’s product. And so, especially during the month of May, let us petition St. Joseph the Worker to pray for us to grow morally and spiritually through the dignity of our work.

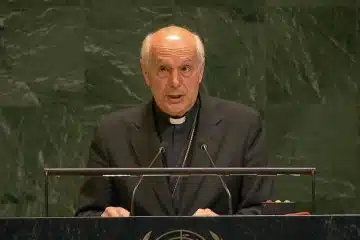

Dr. Kenneth Craycraft is an attorney and the James J. Gardner Family Chair of Moral Theology at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary & School of Theology.

This article appeared in the May 2022 edition of The Catholic Telegraph Magazine. For your complimentary subscription, click here.