Where Secular Meets Sacred

In a visually saturated world, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed and become desensitized to beauty. Visio Divina, Latin for “divine seeing,” encourages us to slow down and engage in visual contemplation, using art as a profound tool for connecting with the Divine.

A Guide to Visio Divina

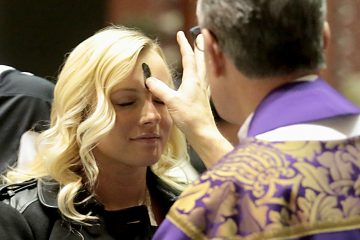

Begin by making the sign of the cross and inviting the Holy Spirit to guide your contemplation. Spend a moment meditating on the Chapel of the Rosary (Chapelle du Rosaire), ca. 1951, by Henri Matisse, located in Vence, France. The chapel is still in use today and is maintained by the Dominican order. Visitors are welcome for a small fee.

Readers are encouraged to look up additional photos of the chapel online, as the images included here can’t fully capture its beauty.

Background

Henri Matisse (1869-1954), obsessed with color and light, spent much of his life chasing beauty. Although born into a Catholic family, he never actively practiced the faith. At times, he identified as an atheist; at others, he was silent on the topic. In general, he seemed private and ambivalent about religion. But when asked by a reporter if he believed in God, Matisse responded, “Yes, when I am working.” He had some sense of God, but no deep relationship with Him.

Matisse’s bold use of color, emotional intensity, competing planes, and fluid line helped define a new movement in art called Fauvism, named after the French word fauve, meaning “wild beast.” Avant-garde for his time, Matisse painted from emotion rather than realism, rejecting the rules of traditional academic art.

His pursuit of beauty can be seen throughout his work, from tropical, vibrant still lifes to more abstract, often sensual, depictions of the human form. “What I dream of is an art of balance, of purity, of tranquility, devoid of disturbing or disquieting subject matter … something like a good armchair, relief from bodily fatigue,” he said.

It’s as if he tried to live inside his paintings—places where pain and suffering could not exist. But in trying to numb all negative emotion, he also kept himself from experiencing the deeper happiness and connection that are only obtainable through truth.

Toward the end of his life, the “perfect” world Matisse had created for himself began to crumble. His health deteriorated. His wife, burdened by his repeated infidelities, left him. And with the world at war again, he fled to the South of France. There, Matisse was forced to face what he had long avoided: the loneliness, emptiness, and discomfort he had spent decades painting over like a bandage.

After surgery for his illness, Matisse found himself in a wheelchair, suddenly unable to manage daily tasks or pursue his art as before. He placed an ad requesting a “young and pretty” nurse. Monique Bourgeois, a young woman discerning religious life, answered the call. As she helped him recover, she posed for several of his pieces, and the two formed a sincere friendship.

Years later, having entered the Dominican order and taken the name Sister Marie-Jacques, she learned that her community needed a chapel. Immediately thinking of Matisse, she asked if he would be willing to design it. As an atheist, Matisse was likely hesitant to take on the project, but he accepted his friend’s offer and soon immersed himself completely. Over the next four years, Matisse poured himself into every detail, from the architecture to the stained-glass windows, the sanctuary murals, and even the priestly vestments.

Enter In

Nestled in the hillside of the South of France, the Chapel of the Rosary takes a modest, rectangular form with a peaked roof, almost like a child’s drawing of a home. Its white, plaster façade and zigzagging, blue-tiled roof contrast with the terracotta rooftops of nearby buildings, giving the chapel a subtle yet distinctive presence.

You step inside. Immediately, you notice how bright it is—stark, yes, but inviting. Sunlight filters through the slender stained-glass windows on the left, casting patches of glittering blues, greens, and yellows across the white walls and tiled floor. It feels as if God continues to co-create with Matisse each day, painting the white- canvassed sanctuary with colorful, dappled light.

On the wall to your right, a large mural, painted with thick, black lines unfolds across white tile. Cloud-like flowers dot the composition and large letters spelling “Ave” hang in the top left corner. Just off center to the right, a loose, delicate drawing of Madonna and Child appears. Mary sweetly holds Jesus, who stretches out His arms in a posture resembling the Cross.

Rows of simple wooden chairs line the aisle, leading your eye toward the altar … only something feels different. The sanctuary is shaped like an “L,” and the altar doesn’t face straight ahead, but diagonally, tucked into the corner where the two walls meet. You walk closer, peeking around the bend to find the short arm of the “L” with a few rows of short pews.

Turning back to face the altar, you notice another mural stretching from floor to ceiling. Black lines form the simple outline of a priest. This is St. Dominic, representing the Dominican Order. Matisse intentionally placed him behind the altar and left his face blank, so that any priest celebrating Mass could see himself in the saint.

As you turn to walk back the way you came, your eyes land on the last mural, this one snaking up the tiled wall—the Stations of the Cross. Each station is numbered and drawn with a trembling hand. The lines feel urgent— loose, jagged, even messy. You sense pain in the strokes, as if Matisse himself was suffering.

And in truth, he was. Still battling illness during the creation of the chapel, Matisse struggled to stand or use his hands for long periods. To make things easier, he attached a brush to the end of a long stick—allowing him to paint while seated, still able to reach the highest points. It’s a quiet example of his devotion: even in his own suffering, he persisted to depict Christ’s.

Reflection

Matisse chased his idea of beauty relentlessly, but when illness and long-suppressed pain finally caught up with him, something unexpected happened. Instead of withdrawing further, Matisse let someone in.

Through his friendship with a young woman who would become a Dominican sister, Matisse didn’t just return to art but stepped into something sacred and real. Designing the Chapel of the Rosary wasn’t a selfish endeavor, but an offering. He was finally honest with himself, pouring his whole being—his vision, creativity, and even his pain—into every

detail. Although he struggled to believe in God, it was this act of beauty—this chapel for a friend and openness toward the Divine—that he later called his “greatest masterpiece.”

What makes the Chapel of the Rosary so beautiful is not just the color or simplicity, but the story behind it. It was created by a man who had spent years trying to avoid suffering and faith, only to be drawn into both by love. His transformation invites us to do the same—to consider that holiness doesn’t always appear in expected ways.

There’s this instinct, I believe, that all human beings possess—an inclination to immediately dismiss something that feels unfamiliar, noting it as strange. We’re drawn to what we understand. We feel safe in the conventional. When we encounter something unusual or abstract, especially in a sacred space, our initial response may be one of hesitation, confusion, or even rejection.

The Chapel of the Rosary invites exactly that kind of tension. There are no ornate carvings, dramatic marble statues, or tiered high altars. The stained-glass windows do not capture biblical stories. Instead, they depict organic shapes glowing in vibrant, cool tones. The walls are not adorned with detailed, richly colored oil paintings hung in gilded frames. Instead, the Madonna and Child, and the Stations of the Cross appear in bold black lines contrasting against the white tile.

Perhaps, it’s not what some expect. And yet, it is holy.

To have a Christ-centered worldview means learning to see truth, goodness, and beauty even when they’re expressed in ways that feel unfamiliar or uncomfortable.

The prophet Isaiah wrote, “He had no beauty or majesty to attract us to Him, nothing in His appearance that we should desire Him. He was despised and rejected by mankind, a man of suffering and familiar with pain” (Is 53:2-3). Christ Himself was not what people expected. He came in humility, clothed in ways the world overlooked and deemed as strange.

Emma Cassani is the graphic designer behind The Catholic Telegraph. She is passionate about exploring the intersection between art and faith.

Emma Cassani is the graphic designer behind The Catholic Telegraph. She is passionate about exploring the intersection between art and faith.

This article appeared in the August 2025 edition of The Catholic Telegraph Magazine. For your complimentary subscription, click here.