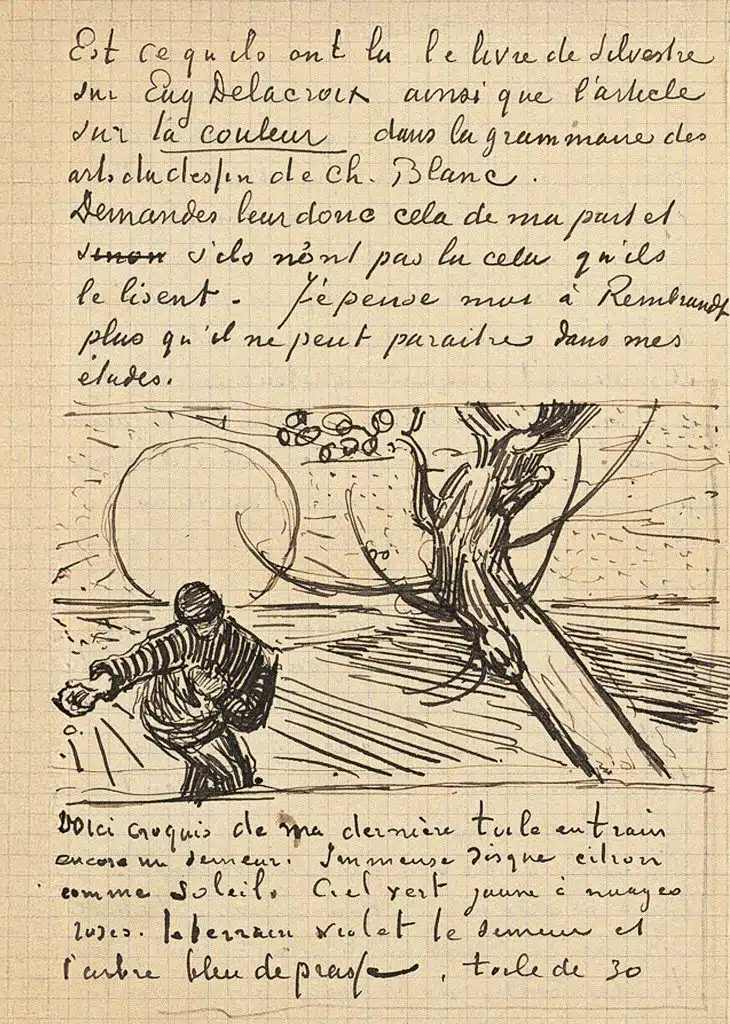

The Sower

In a visually saturated world, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed and become desensitized to beauty. Visio Divina, Latin for “divine seeing,” encourages us to slow down and engage in visual contemplation, using art as a profound tool for connecting with the Divine.

A Guide to Visio Divina

Begin by making the sign of the cross and inviting the Holy Spirit to guide your contemplation. Spend a moment meditating on The Sower (ca. 1888), painted by Vincent Van Gogh. This work is located at the art museum in Zürich, Switzerland. Then, read Matthew 13:1-8 and 13:18-23.

Background

Vincent Van Gogh was born in 1853, the oldest of six children. His father, a minister in the Dutch Reformed Church, raised the family on strong Christian morals. Because they were middle-class, his parents lacked the funds to provide their children with a prestigious education and social standing; instead, they instilled a rigorous work ethic. For Vincent, this pressure became a burden, fueling tension at home and resulting in frequent mental breakdowns.

Like many young people, Vincent struggled to find his vocation. He first tried art-dealing through his uncle, who secured him a position at the international firm, Goupil & Cie. At first, he loved seeing and learning about the artwork that passed through the gallery, but the work soon felt unfulfilling. Drawn more deeply to the faith, he dreamed of becoming a pastor like his father. Vincent attempted theology school but failed the entrance exam, leaving him restless and uncertain once again.

Still feeling called to serve Christianity, Vincent became a missionary in 1878. Immersing himself in the poverty of the Belgian coal miners, he aided the poor and sick and gave away what little he had, even choosing to sleep on the floor. His radical act of humility unsettled the mission leaders, who also criticized him for being short-tempered, disorganized, and poor at communication. Feeling out of place once again, Vincent confided his frustrations in letters to his brother, Theo, often including small sketches. It was Theo who eventually encouraged Vincent to devote himself fully to art.

Taking a new direction, Vincent threw himself into illustration at the age of 27. Knowing almost nothing about drawing, he devoted every hour to practice, reading countless books, and copying the masters. Having quit a drawing class after a month due to constant criticism of his technique, he came to realize that artistic expression mattered more than achieving a rigid academic style. He struggled with money and moved around frequently, still maintaining contact with Theo.

Vincent fell in love with depicting the working class and even dressed like one, which further disappointed his family. “He hoped that his art would reach ordinary folk; he wanted to make figures ‘from the people for the people’” (Vincent van Gogh: A Life in Letters, 36). Inspired by Jean-Francois Millet, who often painted peasants in the fields, Vincent moved to the rural province of Drenthe in the Netherlands.

There, he painted somber rural scenes of peasants, cottages, and Dutch landscapes—his palette, dark and heavy. It wasn’t until 1888, when he moved to Arles in the south of France that he discovered his love for color and light. There, in France’s countryside, Vincent became the Van Gogh we’re more familiar with.

In Arles, he was determined to portray peasant life honestly and in his own style. When he sent his studies to his Dutch friend and fellow artist, Anthony Van Rappard, Rappard’s reaction was harsh: “How dare you invoke Millet and Breton” (Letter 514). To Rappard, who was well-trained and faithful to academic standards, Vincent’s style seemed crude and unworthy of comparison to the greats. But, for Van Gogh, the roughness was intentional—he wanted to capture the rawness of peasant life, not idealize it.

It was also in Arles that he sketched and painted The Sower multiple times. Captivated by this scene, he channeled both his admiration for Millet and his own search for meaning through color and light.

Enter In

Beneath an electric lime sky, the large sun settles into the horizon. As evening draws near, a persistent laborer tends his fields. The air is cool and crisp; he is bundled in dark blue layers of his worker’s attire. He bends and scatters seed with open hands, steadily covering the soil row by row.

Notice the colors—vibrant pastels, humming with vigor. Van Gogh layers complementary hues—purple and yellow, blue and orange, red and green—to heighten the drama of the evening light. At this time, he was particularly inspired by Japanese woodblock prints with their sharply contrasted color, bold line, details of nature, flat perspective, and enlarged forms—which is why the sun appears so exaggerated.

Dr. Michael Banner of the University of Cambridge beautifully observes that the “incandescent colors are meant to communicate the moment’s intensity, as the sower, with the sun forming a halo behind his head, bends to his holy task.” The sun becomes a halo, marking the sower as Christ Himself—or perhaps a saint in the making.

At the end of a ridge, the sower meets a gnarled tree, its branches bare yet budding. The tree seems to mimic his movements, twisting as he twists. Banner notes that “The tree is heavily pollarded, and at certain times of year, might itself seem dead, like the seed. Yet from its wounds fresh blossom springs, holding over the sower’s lowered head a sign of promise… .” The tree cuts the canvas diagonally in two: the sower and sun on one side, the open fields on the other. It feels like a threshold, a reminder of death and the rise to new life.

And then there is the time of day. Farmers normally begin sowing at dawn, yet Van Gogh shows us the task at dusk. Perhaps the sower has labored from morning to evening, scattering seeds until the very last light. Night will fall, but dawn will return with fresh beginnings and new growth.

Reflection

Vincent found wisdom in watching the peasants work in the fields. During his time in the French countryside, he filled sketchbooks with sowers, diggers, and ploughers, determined to capture the dignity of their labor. He believed painting peasants was a serious endeavor—not to be used as decoration but as an art that could give people “serious things to think about” (183, [Letter 497]). To him, the peasants formed a world of their own, “so much better in many respects than the civilized world” (184, [Letter 497]). He was convinced that the city’s art critics had much to learn about life from the humility and perseverance of the country folk.

In one of his many letters to his brother Theo, he describes this newfound wisdom: “In every person who’s healthy and natural, there’s the power to germinate as in a grain of wheat. And so natural life is germinating. What the power to germinate is in wheat, so love is in us” (217, [Letter 574]).

In reflecting on wheat, Vincent was reaching for something universal—the hidden force of life itself. For us as Christians, that life-force is not only natural, but supernatural: it is the Word of God, sown in us by love. In Matthew’s Gospel, Jesus tells us that the seed is the Word, cast freely on every type of soil—the varying conditions of the human heart: hardened, shallow, distracted, or receptive. God the Father is the first and perfect Sower, sending His Son—the Word—into the world, thus initiating the mission of salvation. Christ scattered the seed without waiting for the soil to be worthy. This shows His limitless and merciful love, a love that trusts grace can take root even in the hardest of hearts. God also invites us to share in His work as co-sowers, carrying the same Word into the world so that His harvest may be full.

Vincent’s words bring a tender layer to this parable. Just as a grain of wheat contains the hidden power to sprout, so too, love lies within each of us, waiting to germinate. The Word of God, when planted in the good soil of our hearts, awakens this love and bears much fruit. The peasants he admired— those who labored to sow, reap, and live close to the earth— become for us reminders of this truth: that life itself is a field, entrusted to our care. We are called to be both the good soil and the sower—receiving God’s Word with openness and scattering it freely in love.

Looking back at Vincent’s life, he constantly wrestled with his faith and finding his place in the world, often comparing himself to a free bird trapped in a cage. Even though his vocation did not take traditional form, he fulfilled it through his art, preaching through color and canvas.

Like Vincent, our ways of spreading the seeds of faith may differ, yet all of us are called to sow, no matter our vocation or stage of life. In homes and workplaces, in friendships and quiet encounters, each of us carries seeds of the Living Word. The question Van Gogh’s painting invokes is simple yet searching: how are you spreading the seeds of faith? ✣