Divine Seeing: Praying with Sacred Art

In a world oversaturated with visual content, we can become so desensitized to images that slowing down to fully appreciate art becomes a daunting task. Many people breeze through museums, galleries and churches, missing opportunities to not only engage with art, but also embrace a profound tool for connecting with the Divine: visio divina, Latin for “divine seeing.”

This prayer form engages individuals in visual contemplation, often offering prayers, referencing scripture, analyzing art and drawing upon the historical context of the artwork, artist, time period or depicted saint.

A Guide to Visio Divina

To begin, make the sign of the cross, inviting the Holy Spirit to illuminate your heart and guide your eyes as you contemplate the artwork. Take a moment to sit with the painting and draw your own conclusions on its subjects and narrative.

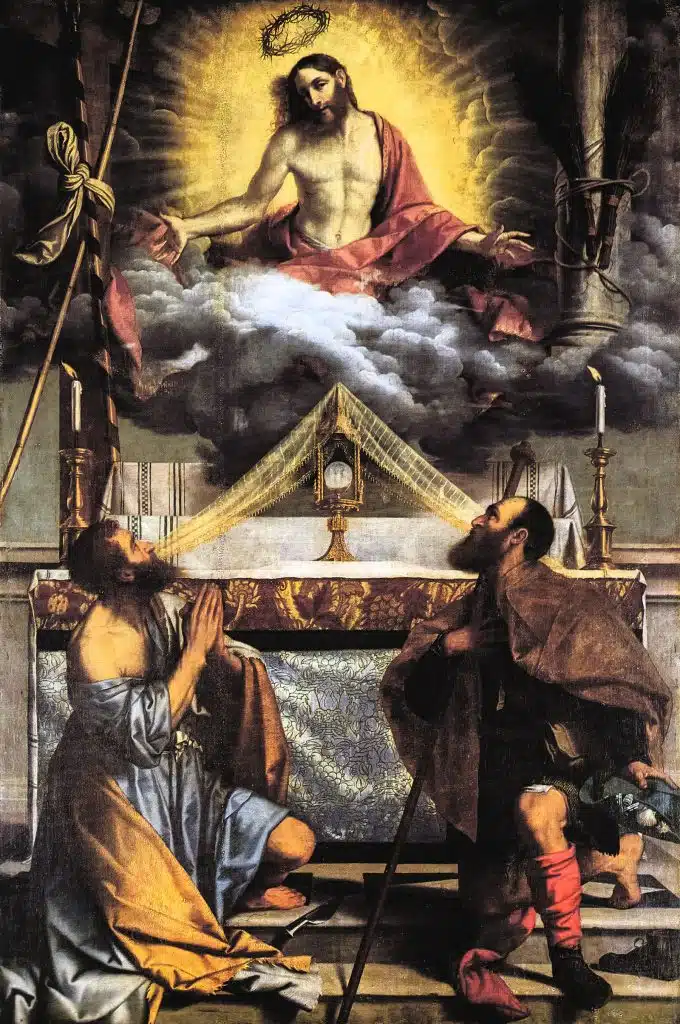

The artwork chosen for this meditation is a lesser-known painting called Christ with the Eucharist and Saints Bartholomew and Roch by Alessandro Bonvicino—more commonly known as Moretto da Brescia. This large oil painting, created during the Renaissance period, was likely commissioned by archpriest Donato Savallo, and still resides at its original parish, San Bartolomeo, in Castenedolo, Italy.

Historical Context

The Protestant Reformation in 1517 led to a decline in Catholic art’s popularity due to iconoclasm—the rejection or destruction of religious images by some Protestant groups. Despite this, Catholic artists persisted, creating works that served for meditation and devotion among Catholics and provided comfort and clarity.

Amid this period of uncertainty, Moretto boldly crafted Savallo’s commissioned piece in 1545, coinciding with the onset of the Council of Trent (1545-1563). Moretto and Savallo predicted the Council of Trent’s verdict on the Eucharist, reflecting the Church’s long-standing beliefs.

St. Bartholomew’s presence in the painting is attributed to the parish for which the artwork was commissioned. St. Roch is included because the parish housed a brotherhood devoted to St. Roch, and his presence is particularly significant given the plague outbreaks of the time that prompted many to seek St. Roch’s intercession for miraculous healing.

Art Analysis + Meaning

Moretto masterfully captures the truth and beauty of Eucharistic Adoration, focusing on the Catholic fundamental of Transubstantiation, where the substance of bread and wine become Christ’s Body, Blood, Soul and Divinity at the moment of consecration, and the accidents—appearance of bread and wine—still remain.

The composition is horizontally divided into two realms: the heavenly (top) and the earthly (bottom), which are bridged by the veiled monstrance to emphasize the Eucharist’s miracle of bringing heaven to earth. The veil represents a metaphorical partition between heaven and earth, concealing the supernatural—what is beyond our physical perception. It reflects the Jewish tradition in which the Holy of Holies contained a veiled tabernacle holding the Ark of the Covenant: “The curtain shall separate for you the holy place from the Most Holy” (Ex. 26:33-34).

In the top center, Christ resurrected emerges from billowing clouds and radiant light, arms open in invitation, exuding a gentle-yet-powerful presence. Surrounding Him, images unfold scenes from His Passion: the scourging implement and pillar, the spear that pierced Christ’s side, the reed that held the wine- soaked sponge with hyssop, the Cross itself, and notably, the crown of thorns depicted as His halo. These poignant images of His suffering emphasize the sacrifice that underpins the Eucharistic celebration.

Christ above the monstrance is not merely symbolic, but suggests a tangible occurrence in the natural world, as indicated by the movement of the altar candle’s flames and Christ’s flowing hair stirred by the wind within the church. This reinforces the reality of the Eucharist’s presence: though unseen, Christ is bodily present. “I am the living bread that came down from heaven” (Jn. 6:51).

St. Bartholomew, one of the 12 apostles, is pictured on the viewer’s left, identified by the knife at his feet—a symbol of his martyrdom during which he was skinned alive. With hands clasped, his eyes look up toward the physical Christ in awe.

St. Roch, depicted with traveler’s attire and bandaged knee, kneels beside St. Bartholomew. A pilgrim known for miraculous healings amid his own plague, St. Roch exudes reverence with hand over heart and hat in hand, gazing up to Christ.

The alignment of Bartholomew, Roch and Christ form a triangle, the saints at the base and Christ at the apex, symbolizing Christ as the Source and Summit and Eucharistic worship forming the foundation of the faith.

Close in Prayer

After exploring the historical context and art analysis as done above, remain still and converse with God. Offer a prayer of gratitude and end with the sign of the cross.

Emma Cassani is the graphic designer behind The Catholic Telegraph, and is passionate about exploring the intersection between art and faith. In 2023, she wrote a visio divina series for The Ultimate Guide to Lent. She finds joy in both learning and guiding others toward a deeper understanding of their faith journey through sacred art.

Emma Cassani is the graphic designer behind The Catholic Telegraph, and is passionate about exploring the intersection between art and faith. In 2023, she wrote a visio divina series for The Ultimate Guide to Lent. She finds joy in both learning and guiding others toward a deeper understanding of their faith journey through sacred art.

This article appeared in the June 2024 edition of The Catholic Telegraph Magazine. For your complimentary subscription, click here.