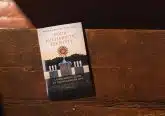

Book Review: The Mass of the Early Christians

This book review starts with a two-part quiz: In the New Testament (1) what is the earliest appearance of the words in the Consecration of the Eucharist, and (2) who said them? If your answer is (1) one of the synoptic Gospels as the earliest appearance and (2) Jesus—of course!—is the person who said them, you can be excused. But you are mistaken; it is an understandable misstep. We know the words of Consecration were instituted by Jesus at what we now call the Last Supper, as recorded in Matthew 26, Mark 14, and Luke 22. The priest says these familiar words every day at Mass, as the bread and wine are transubstantiated into the Precious Body and Blood of our Lord.

But the earliest appearance, by date, of the words spoken during the Consecration of the Eucharist is not in one of the Gospels; it’s in the first letter of St. Paul to the Corinthians, which was probably written around A.D. 56. The earliest Gospel—Mark—was probably written some 15 years later, with Matthew and Luke coming some years after that. Thus, the very first appearance in writing of these words was communicated not by one of the evangelists, but by the first missionary to the Gentiles, in First Corinthians 11:23-26.

In his timeless book, The Mass of the Early Christians, recently reissued in a third edition, Mike Aquilina makes special note about this first appearance of the words of Consecration: occurring in Paul’s letter, they give us important information about both the Eucharist and the living oral tradition that guarded and transmitted those words even before Jesus was later quoted in the Gospels. As Aquilina notes, “We see the care with which ritual form was passed from culture to culture” in the early Church through the Jewish convert Paul’s writing to his Gentile flock at Corinth. This care and preservation of the words of Consecration tell us that the early Church did not form around a book, but rather around a feast—the feast of the Body and Blood of Christ. “That passage from Paul shows not only the care of the early Christians for the liturgy but also the reason for their care,” observes Aquilina. “Moreover,” he continues, “Paul emphasizes that this action will be at the center of the new order he [Jesus] is establishing with his death and resurrection.”

Thus does Aquilina set the tone for this highly readable and deeply informative early history of the Church’s celebration and promulgation of the Mass. As with all of his dozens of books, Aquilina engages a broad range of early sources to show both the Mass’ continuity, and deep reverence in which it was held by the early, developing Church. As he acknowledges, we do not have a clear and certain form of the entire liturgy from those earliest days. But we do know that the words of Consecration were always at its center, with everything else in the developing liturgy built around the Consecration of the Eucharist, the summit of our faith.

For me, the highlight of the book is the last chapter (33, which cannot be a coincidence), in which Aquilina takes us into a reconstruction of what a first-century Mass might have looked like. This is not mere speculation, as he builds this scenario from a close reading of the theologians and councils through which the liturgy was developed and preserved. This tour through the earliest treatment of the Mass gives us fresh eyes through which to see and understand our own participation in the “medicine of immortality,” as St. Ignatius of Antioch put it. As such, one might call The Mass of the Early Christians a handbook companion for the care of the soul. ✣

This article appeared in the November 2025 edition of The Catholic Telegraph Magazine. For your complimentary subscription, click here.