Moonlight Musings

During the 12 years I lived and worked with the Pope’s astronomers at the Vatican Observatory, located 15 miles outside of Rome at Castel Gandolfo, I had the privilege of welcoming many visitors. People loved seeing the four beautiful and historic telescopes housed under retractable domes atop the Papal Palace and in the nearby Pontifical Villas.

During the 12 years I lived and worked with the Pope’s astronomers at the Vatican Observatory, located 15 miles outside of Rome at Castel Gandolfo, I had the privilege of welcoming many visitors. People loved seeing the four beautiful and historic telescopes housed under retractable domes atop the Papal Palace and in the nearby Pontifical Villas.

They also enjoyed looking at the Observatory’s large meteorite collection, as well as its astronomical library and historic astronomical instruments display. But, at some point during a visit someone always asked, “Why on earth does the Pope have an astronomical observatory? Aren’t science and religion opposed? Aren’t they in conflict?” To which I replied: “The reason why the Pope has an astronomical observatory is that it would cost too much for him to have a particle accelerator!”

Science and faith are not opposed to each other; they’re on the same team, they’re both seeking the truth!

Science was part of my faith life and is part of my vocation story. I grew up as a “cradle Catholic” on the West Side of Cincinnati and attended St. Jude grade school and St. Xavier High School. But while a college student at a non- Catholic university, I reacted against my Catholic upbringing. It seemed to me that religion and the Church were full of hypocrisy, and I wanted nothing to do with them. The strange thing is that I was led back to faith, in part, through my study of science.

I majored in physics and loved it. Amazed by the deep connections between mathematics and nature, I was bowled over by the power and beauty of the physical theories of Newton, Maxwell, Einstein, Schrodinger and others. In the back of my mind, however, there were nagging questions: Why does mathematics, which is a human creation, match up so well with physical reality? Why are scientific theories so beautiful? Could it have been otherwise? Does it have to be that way?

In my senior year at college, I became torn between pursuing a PhD in physics or entering the Jesuits. The Jesuits won, and I thought I was done with physics. But during my long years of Jesuit training, science was the best way for me to work my way into studying philosophy and theology. Physics often helped me understand and care about the questions being raised by philosophy and theology. Later on, as a newly ordained priest, the Jesuits sent me to earn a PhD at the University of Chicago in the interdisciplinary field of history and philosophy of science.

The bottom-line is that science and religion were always tangled together for me; each raising questions for the other to address, each making the other more interesting. I never had a sense that science and religion are in conflict. Sure, some religious people claim, on the basis of the Bible, that a particular scientific theory should be true or false. And sure, some scientists declare, on the basis of science, that God does or does not exist or that a particular human action is morally right or wrong. But these aren’t cases of true conflict between science and faith—these are cases of people making mistakes, of people “not getting it.”

St. Augustine of Hippo observed 1600 years ago that results from science should be taken into account when interpreting the Bible. In 1870, Ecumenical Council Vatican I declared that no real conflict can ever exist between faith and science. In 1893, Pope Leo XIII declared that if faith and science seem to be at odds, and we can’t resolve the conflict, we shouldn’t panic, but instead suspend judgment for the time being. After all, the God who inspired sacred Scripture is the same God who created the natural world, and God doesn’t contradict God. In 1988, Pope St. John Paul II wrote, “Science can purify religion from error and superstition; religion can purify science from idolatry and false absolutes. Each can draw the other into a wider world, a world in which both can flourish.”

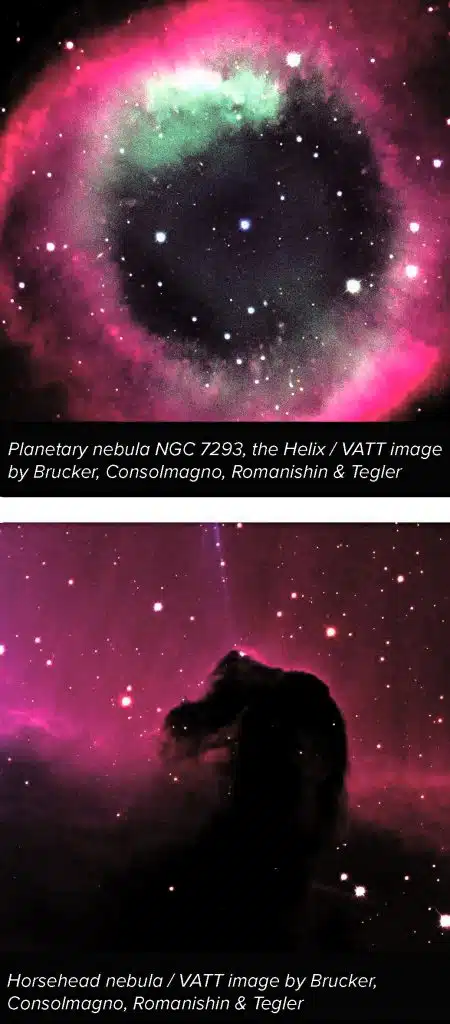

During my time at the Vatican Observatory, I was fascinated by the differences between its two modern locations. The Observatory’s headquarters are at Castel Gandolfo, with four beautiful historic telescopes and close proximity to Vatican colleagues. The Observatory’s modern telescope is located outside of Tucson AZ, atop Mt. Graham, as part of an official affiliation relationship with the department of astronomy at the University of Arizona. At Castel Gandolfo, the Jesuit astronomers live in a 400 year old building, and at times, they meet with the Pope and other Vatican officials. At Tucson, the Jesuit astronomers live in an adobe house in a residential neighborhood, working side-by-side with professional astronomical colleagues in a thoroughly secular environment. At Castel Gandolfo, cardinals and bishops ask for help in understanding what science means for the Church. In Tucson, scientists and students ask for help in understanding what religion might mean for science.

Since 2022, I have lived and worked in central Rome and am now the religious superior of the Jesuit community of the Pontifical Biblical Institute, which was founded by Pope Pius X in 1909. I also teach part-time at the Pontifical Gregorian University. What makes me laugh is this: The curriculum and research of the Pontifical Biblical Institute are organized around a particular kind of scientific approach to studying the Holy Scriptures. So, after 12 years at the Vatican Observatory living with Jesuit “science nerds,” now I’m living with Jesuit “Bible nerds”! This somehow reassures me that God has a sense of humor—which in turn reassures me that God is really there!

This article appeared in the April 2024 edition of The Catholic Telegraph Magazine. For your complimentary subscription, click here.