A Closer Look: The Purcell Brothers, Abolition and The Catholic Telegraph

“History” is not the accumulation of facts in the past, but rather what we say about, and the use we put to, those facts. This is not to say the facts are unimportant, nor should they be manipulated by the historian. A conscientious historian wants to be as thorough and careful as possible so the story she tells about the past is not distorted. But she will necessarily have to use critical discernment about how to present those facts, including such factors as the political, economic, social and demographic contingencies in which they are discovered. While it is neither her role to excuse nor judge the people whose story she tells, the careful historian does contextualize her subjects in order to try to understand their motivations and intentions. Perhaps most importantly, the historian’s work allows us to learn how we have become who we are in order to try to become who we should be.

THE PURCELL BROTHERS

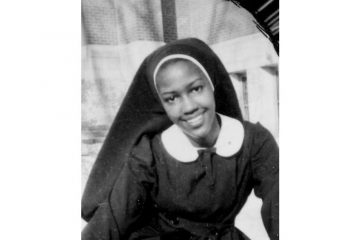

The story of Archbishop John Baptist Purcell and his brother, Father Edward Purcell, as it pertains to the 19th Century abolitionist movement, is an excellent example of this understanding of history. While they were far from perfect and their story leaves us wishing they had done more for the cause of emancipation, the moral integrity of these two fine priests leaves a positive legacy. And it puts the Archdiocese of Cincinnati and The Catholic Telegraph squarely in the story of African American history during and after the Civil War.

John Purcell was Bishop of the Diocese of Cincinnati from 1833 until Cincinnati was made an archdiocese in 1850, after which he was archbishop until his death in 1883. Father Edward Purcell was a priest of the archdiocese and editor of The Catholic Telegraph from 1840 to 1879. With their respective platforms, the Purcell brothers became the first and leading Catholic voices in the United States for the abolition of slavery and the emancipation of slaves. As Father David Endres wrote in his Ohio Valley History article, “Rectifying the Fatal Contrast: Archbishop John Purcell and the Slavery Controversy among Catholics in Civil War Cincinnati,” after “mild protestations against slavery, [Archbishop] Purcell became an outspoken proponent of . . . emancipation.”

As early as 1838, for example, Archbishop Purcell delivered a speech in which he condemned the “virus” of slavery. But, noted Father Endres, when The Catholic Telegraph reported the speech (presumably under the guidance of Purcell) it hedged on the question of emancipation, noting that, “however desirable,” prudence counseled against it at that time. And Archbishop Purcell “refrained from taking a vocal stand in the decades before the war,” explained Father Endres. Like many of his brother bishops, Purcell feared the political, economic and social upheaval that sudden emancipation would cause. Of course, from our perspective, this reticence is indefensible. Fundamental human liberty should not be subject to such considerations.

THE TELEGRAPH CONDEMNS SLAVERY

THE TELEGRAPH CONDEMNS SLAVERY

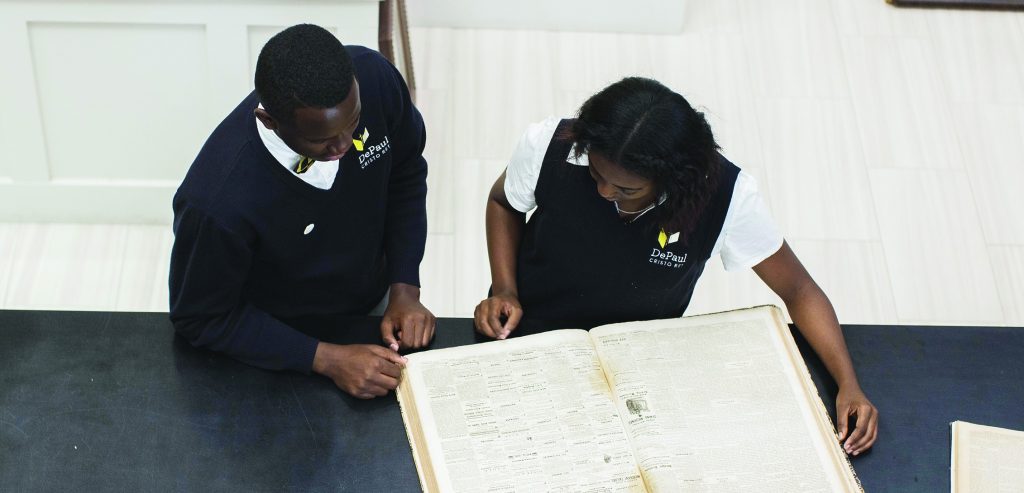

But while it regrettably did not occur earlier, these attitudes changed dramatically over the years until about 1860, when Archbishop Purcell became the leading Catholic prelate for the cause for emancipation in the U.S. Church. The Sept. 3, 1862 edition of The Catholic Telegraph, for example, published a lecture by the archbishop, condemning the “sin of . . . holding millions of human beings in physical and spiritual bondage.” And in an April 22, 1863 editorial, probably jointly written by the Purcell brothers, The Telegraph became the first diocesan Catholic newspaper expressly to condemn slavery and support immediate emancipation.

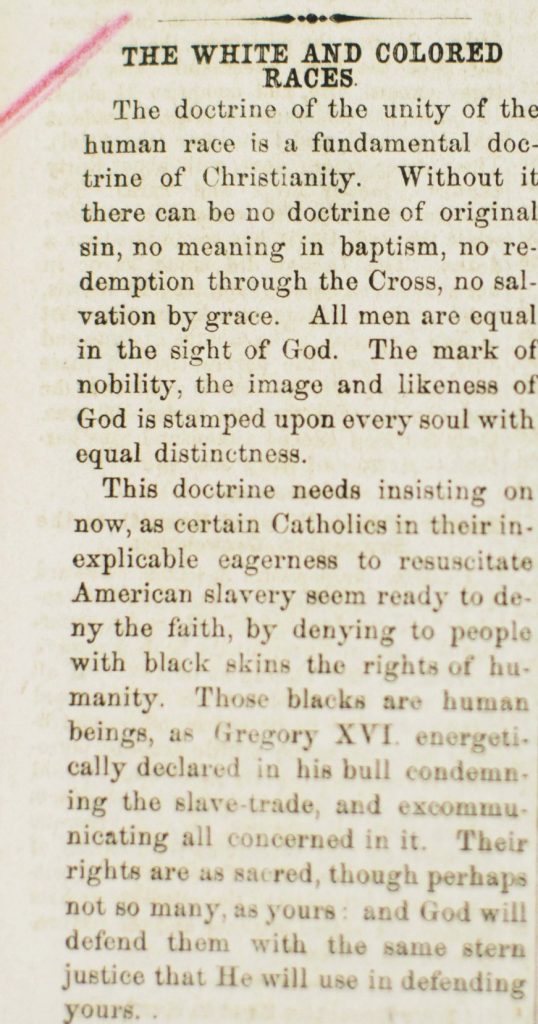

In “The Church and the Oppressed,” the paper opined that “the doctrine of the unity of the human race [is] a fundamental doctrine of Christianity,” and that, therefore, no historical contingencies or contexts can justify the continuation of slavery. The following Sept. 9, another editorial declared, “The mark of nobility, the image and likeness of God is stamped on every soul. It implies equality in all that is essential to manhood, equality in origin, equality in destiny, and in the right to means of fulfilling the destiny.”

While it may seem like an unexceptional declaration in 2020, in 1863 the archbishop’s uncompromising stand drew widespread criticism within the hierarchy of the Church in the U.S., to the shame of other bishops and the credit of Archbishop Purcell. And even though he met resistance in his own archdiocese, Father Endres explained, Archbishop Purcell “was successful in bringing attention to the moral and social ramifications of the slavery question.” And he demonstrated that “some Catholics were willing to stand in support of emancipation and the honor of the nation,” concluded Father Endres.

We can, and should, regret Archbishop Purcell’s inertia before the Civil War. But we can also learn from it, using it as a cautionary tale about our own resistance to eliminating barriers to racial progress, regardless of how subtle they may be. And, while we do not deny that this lethargy clouds his legacy, we also must affirm his moral growth and recognize the positive contributions of Archbishop John Purcell – along with his brother, Father Edward Purcell – to the story of African Americans in the Archdiocese of Cincinnati and beyond.

DR. KENNETH CRAYCRAFT is an attorney and the James J. Gardner Family Chair of Moral Theology at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary & School of Theology. He holds a Ph.D. in moral theology from Boston College, and a J.D. from Duke University School of Law.

DR. KENNETH CRAYCRAFT is an attorney and the James J. Gardner Family Chair of Moral Theology at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary & School of Theology. He holds a Ph.D. in moral theology from Boston College, and a J.D. from Duke University School of Law.

This article originally appeared in the November edition of The Catholic Telegraph Magazine. For your complimentary subscription, click here.