A Painful Past, a Call to Healing

Learning from the Story of the Randolph Freedpeople

by John Stegeman

Within the long history of slavery and racism in the United States, there are thousands of rarely told stories. One such story is that of the Randolph Freedpeople.

Thanks to an exhibit hosted by the Missionaries of the Precious Blood and Sisters of the Precious Blood, the Archdiocese of Cincinnati Anti-Racism Task Force was able to embark on a pilgrimage to Carthagena this past September, to learn about this tragic story and the lessons it still holds for today.

Who were the Randolph Freedpeople?

The Randolph Freedpeople were enslaved men, women, and children (about 400 people) emancipated upon the death of their enslaver, John Randolph, in 1833. Randolph not only restored their freedom, he procured substantial lands for them in Mercer County.

However, because Randolph left conflicting wills concerning their emancipation, it took 12 years of court processes before they were freed.

Then, starting in Virginia, the group endured hardships on a lengthy journey by wagon, paddleboat, canal barge, and on foot before reaching New Bremen, where 3,200 acres awaited them. As they camped in tents along the way, they hoped the end of their journey would be a fresh start.

Sadly, instead of a happy ending, they were met in New Bremen by an angry mob that refused to let them settle in the area. Local residents even passed resolutions resolving not to share their community with black people.

The group ended up settling in Piqua, Troy, and other communities well north of Cincinnati, which were also sites of racial unrest at the time. Still, the freed individuals found jobs and settled where they could, integrating into surrounding communities.

Early in the 1900s, surviving members of the group hosted reunions and eventually mounted legal challenges for the return of their promised land. Their case made it to the Ohio Supreme Court, but it ruled that the case’s statute of limitations had expired, so the group was never granted restitution.

The Pilgrimage

In September, the Anti-Racism Task Force brought approximately 70 people on the Pilgrimage for Racial Justice. They began at the St. Charles Center in Carthagena, which was founded by Charles Moore, who was himself formerly enslaved. At each stop, pilgrims learned the location’s significance then had time for prayer and reflection on Church teaching.

The first station of the pilgrimage taught the history of the first black settlers in that area of Ohio in Mercer County. Next, the group visited a black cemetery that predated the Civil War and sits adjacent to St. Aloysius Catholic Church and its cemetery. Andrew Musgrave, director of the Catholic Social Action Office, couldn’t help but notice the stark contrast between the cemeteries’ preservation.

“This church has, like a lot of older churches do, a cemetery,” he said, noting that it is well maintained and respected. “But off to the side is the black cemetery; much of it is in disrepair and disregard.”

The pilgrims next visited the former Emlen Institute, a school that taught black and Native American students in the 1840s. It moved to Pennsylvania in 1857, and its land became home to the Congregation of the Most Precious Blood.

The final exhibit on the tour highlighted the Randolph Freedpeople. The pilgrimage ended with Mass with the Church of the Resurrection Choir.

The Impact

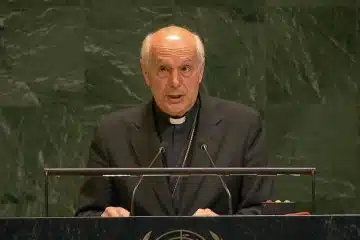

Precious Blood Fr. Tom Hemm was instrumental in bringing the Randolph exhibit to the St. Charles Center and noted that pilgrimages like this help us remember our “sinful past.”

“This is a very grounded way to say, wait a minute, this happened here,” Fr. Hemm said. “The challenge, of course, is people will say, ‘Well, that was then, and what do we do now?’ But the Church itself is much more vocal now about the needs for reparation and reconciliation; and that we not forget and that we seek healing today.”

Musgrave echoed that sentiment, noting several reasons it is important to keep tragic parts of the past in mind.

“We recognize and honor that every single person, regardless of race, nation, and creed is born in and has the image and likeness of God—has dignity from God,” Musgrave said. “Our Church, while not unique among churches, is definitely at the forefront of talking about and advocating the dignity of all people from the first moment of conception to the last moment of natural breath. We have a commitment to that in a myriad of ways, and our Church does tremendous work in honoring the dignity of others.”

It is incumbent upon us to look back in history, Musgrave said, to see when people failed and recognize that there were flaws both within the Church and the broader culture and community that allowed or led to the perpetration of injustice.

“History is rife with examples of injustices rearing their ugly head at different times over different periods and largely because people were ignorant of what happened in the past,” he said. “Today, maybe because people are not aware of it—or don’t acknowledge it, or don’t believe it, or don’t care— injustice persists. I think in the Randolph Freedpeople case, you have an example of a group of human beings born with God’s dignity, who were treated with the utmost disrespect, neglected, and treated as less than human.

“If we don’t recognize that and remember that and learn from that, it is bound to happen again.”

The Anti-Racism Task Force meets on the fourth Monday of each month. If you are interested in joining their discussions, contact the Catholic Social Action Office at [email protected].

This article appeared in the February 2026 edition of The Catholic Telegraph Magazine. For your complimentary subscription, click here.