Slavery: A Moral Virus

The following is a modified version of an article written by Father Earl Fernandes for The Catholic Telegraph in Feb. 2011.

The following is a modified version of an article written by Father Earl Fernandes for The Catholic Telegraph in Feb. 2011.

The U.S. has a rich history of freedom. Still, every nation’s history is filled with shadows and light; great evils have been tolerated and even perpetuated. This year marks the 160th anniversary of the start of the Civil War and the 200th anniversary of the Archdiocese of Cincinnati. Amid the racial tension and civic unrest currently plaguing our country, it is important to reflect on a certain historical moment in our archdiocese to discern what role, we, the people of the Archdiocese of Cincinnati, might play in constructing a more just society, one in which we see one another as brothers and sisters.

A DARK ERA

The presence of slavery and its legacy cast a shadow over a country which holds out the light of liberty to so many. Though not perfect, the Archdiocese of Cincinnati has a rich history. A light in that dark era of slavery and the Civil War was Archbishop John Baptist Purcell, bishop of Cincinnati from 1833- 1883. Archbishop Purcell’s record was mixed. Early in his episcopacy, he did not favor emancipation; he criticized abolitionists for their extremism and anti-Catholicism. He spoke only of preserving the Union and avoiding violence, even if compromise was necessary.

Archbishop Purcell had to attend prudently to the needs of his flock, including an influx of Irish Catholics, who were the lowest class

in society and who feared free blacks would compete with them for jobs, and so for many years he did not publicly support emancipation. One is tempted to think of him as slow to act and not at all a champion of racial equality.

Still, Archbishop Purcell’s own sentiments can be gleaned from an 1838 speech he gave in his home town of Mallow, Ireland. While speaking, he lamented the inconsistency between the “admission in the American charter which said ‘that all men were born free’ and that the existence of slavery in that country.” Archbishop Purcell condemned slavery in principle as degrading, calling it a “moral virus,” not introduced by Americans; still, he felt that for prudential reasons such an evil could not be eliminated easily.

For nearly 25 years, he was silent on the subject of slavery. In May 1862, Archbishop Purcell journeyed to Rome. While there, he met Bishop Dupanloup of Orléans, who sharply criticized American slavery. The encounter profoundly influenced Archbishop Purcell; it caused him to “get his Irish up”. Upon his return, he gave a lecture, “Impressions of Europe,” at Pike’s Opera House.

TURNING TO EMANCIPATION

During the lecture, Archbishop Purcell responded to European criticisms of America, arguing that despite its imperfections, the American government was still superior to anything Europe offered. Europeans criticized the discrepancy between the Constitution’s tolerance of slavery and the Declaration of Independence. Archbishop Purcell said that the South “…kept millions of men in bondage, forbidding them to marry, which St. Paul calls a doctrine of devils, and forbidding them to be educated.” He showed how the South had been uncompromising and how the North could have declared the slaves emancipated and provided them with arms, but for the sake of humanity refrained. In contrast, the South was “imitating her perfidious friends in Great Britain,” who had persecuted, subjugated and starved Archbishop Purcell’s own people.

Archbishop Purcell’s speech drew hostile criticism from Catholic and non-Catholic quarters. He prudentially held his tongue, but

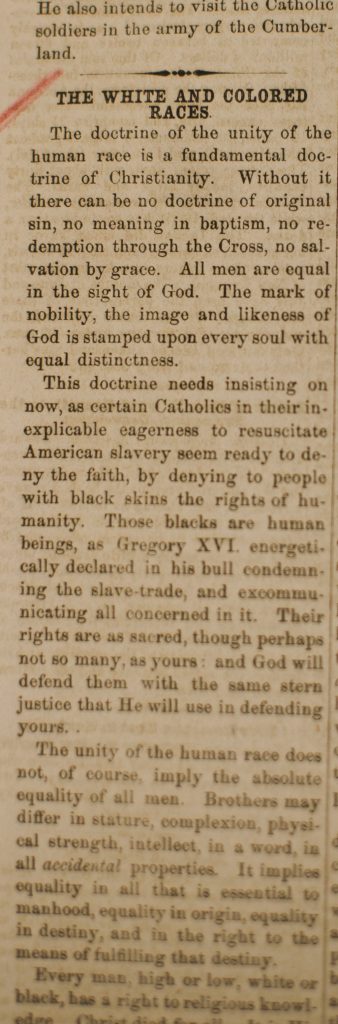

The Catholic Telegraph began its move from opposition to emancipation to favoring abolition of slavery. The Church in Cincinnati began taking a stronger stand in favor of the dignity of the human person. This stand emerged not from politics but from principle and from Archbishop Purcell’s sense as an Irishman of solidarity with an oppressed people. The Church found her voice to speak up against a great evil.

We are the heirs to that legacy. In history, the Church is filled with light and shadows. Archbishop Purcell’s example teaches that in the face of evil, one cannot forever remain silent. In January, people march against the injustice of abortion, and in February, Black History month, we remember the contributions made to our country by those once deemed by the courts to be “property”. This June, as we celebrate our archdiocese’s bicentennial, and, as we move toward Independence Day, we learn from the “faith of our fathers.” Archbishop Purcell reminds us that it is the task of all Catholics to affirm the self-evident truth that “all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Father Earl K. Fernandes is the pastor of St. Ignatius of Loyola Church in Cincinnati and holds a doctorate in moral theology from the Alphonsian Academy in Rome.

Father Earl K. Fernandes is the pastor of St. Ignatius of Loyola Church in Cincinnati and holds a doctorate in moral theology from the Alphonsian Academy in Rome.

This article appeared in the June 2021 Bicentennial edition of The Catholic Telegraph Magazine. For your complimentary subscription, click here.